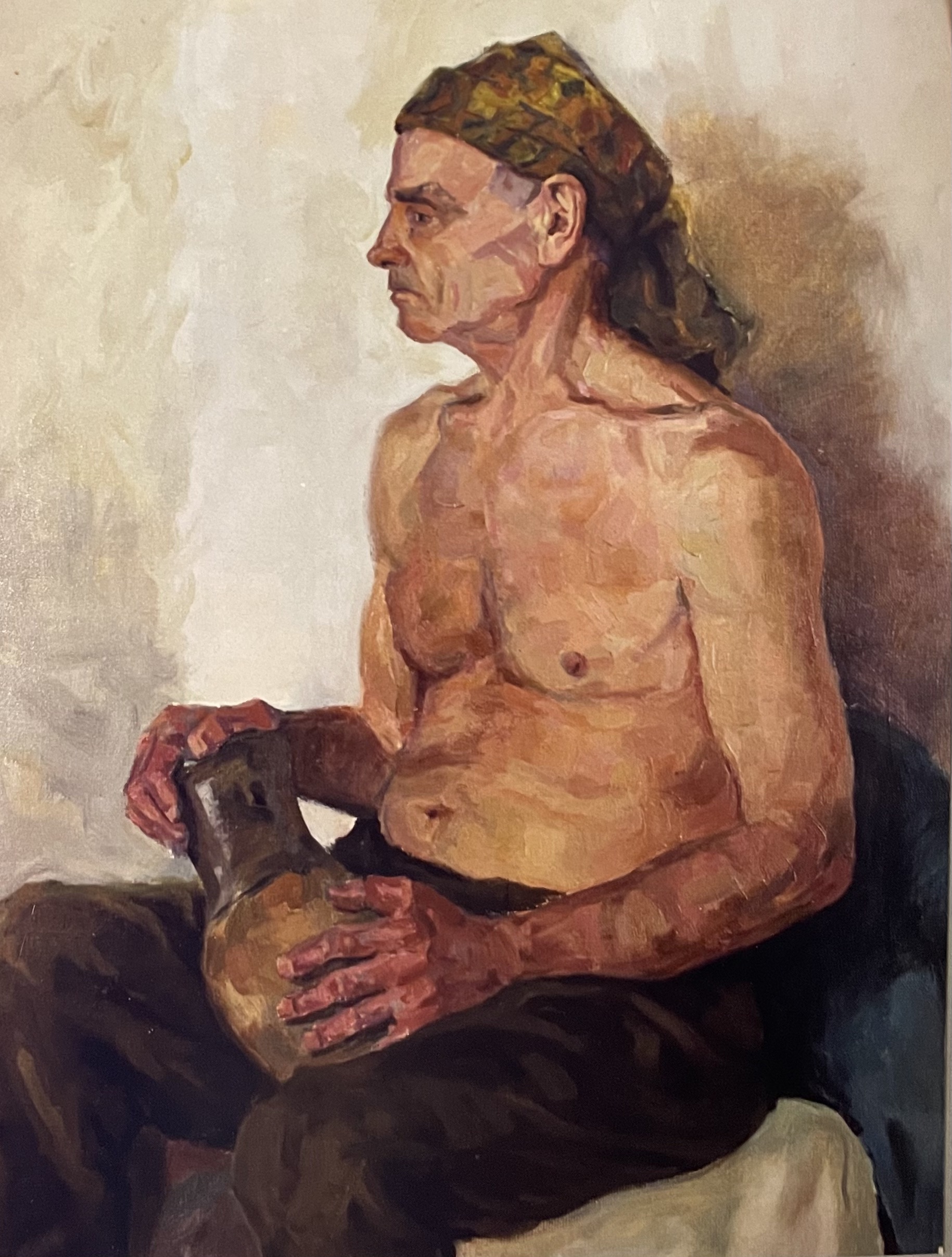

Oleksiy Koval, 1996

Oil on canvas, 80 x 60 cm

State Art School, Kyiv

Photo: Volodymyr Myshko

PING PONG

Oleksiy Koval in interview with Selima Niggl¹

¹ This interview was conducted by e-mail during the period from February 26 to June 15 2023, between the locations of Munich, Augsburg, Rostock, Milan, Istanbul, Penna San Giovanni (Marche) and San Pancrazio (Tuscany).

S.N.:

I am interested to know where you come from and how you came to painting. So, who are your parents and grandparents? What do they do, or have they done? Where did your decision to study art come from?

O.K.:

I was born in Soviet Kyiv. My mother was educated as an interior designer and my father is an illustrator and book designer. Both my grandmothers were medical doctors. My grandfather was a Soviet artillery officer in World War 2, and later he worked as a locksmith in a Kyiv factory.

I came to painting when I was three years old. I was allowed to paint with gouache from my father. Then my parents enrolled me at the Kyiv Palace of Pioneers. There, children and young people could get a kind of early education in fine arts, music and dance. The level of education was abysmal, although the Palace of Pioneers was a central place for gifted children in the Soviet Union. For example, when I painted grey tires on a city bus with gouache they were too square for my teacher, and he very roughly touched them up with a soft pencil on the page. When I was supposed to depict my hometown in class, I painted green city hills with the huge golden crosses and onion domes of Orthodox churches and cathedrals. The teachers not only threw away this sheet, but also invited my parents to a conversation: “why does your son paint Orthodox crosses instead of Soviet stars?” As a result, I no longer visited the Palace of Pioneers.

After finishing elementary school education, at the age of ten I passed the entrance exams for the State Art School of Taras Shevchenko in Kyiv. For this, one had to master the technique (manner) of socialist realism. Half a year before the exams I took private lessons in watercolor painting, drawing and composition of socialist realism.

After eight years I graduated from art school and was enrolled at the Kyiv Academy of Arts. Although Ukraine was no longer part of the Soviet Union at that time, fine arts education at the universities still remained very Soviet. For this reason, I applied to the Art Academy in Munich and was accepted.

The decision to study art, in my opinion, came immediately and can be found in my everyday painting and drawing.

S.N.:

Were you already aware – as your words suggest – that socialist realism would not be your path during your training at the Kyiv Art Academy? Do skills and techniques you learned during that time still play a role in what you do today? If so, in what way?

O.K.:

Yes, I was aware even before I started my studies at the Kyiv State Art School that socialist realism would not be my path. Socialist realism was already dead in the second half of the 80s. Socialist realism is simple: you don’t need to think about what to do, you just need to focus on how to do it. It is ultimately about craft. I can teach you that craft, and you’ll master socialist realism in half a year. If you are really untalented, it will take you two years at most. The most devoted and successful artisans of the Communist Party, like Tetyana Yablonska, for example, have not been able to remain faithful to socialist realism. When Yablonska started to deal with the “what do I do?” question, she arrived between Impressionism and Symbolism. Almost 100 years after the two art movements were created! I found it awful then and I still find it unbearable today: socialist realism sometimes delivered impressive craftsmen, but usually embarrassing and mediocre painters. That’s why I always worked on my own compositions in parallel with the assignments both at the art school and at the art academy in Kyiv. But I don’t want to give the impression that the Art Academy in Kyiv only taught socialist realism in the 90s. Among other things, one had lessons in anatomy, perspective, monumental and Christian Orthodox painting, compulsory lectures in art history, philosophy, and religious studies. I learned a lot during my studies in Kyiv. I apply this knowledge and experience directly and indirectly in my painting today: Division of the surface, theories of proportion and contrast, countless painting techniques.

S.N.:

Were you at the Munich Art Academy with Jerry Zeniuk from the very beginning? Why did you choose to study with him and not take other painting classes like those with Hans Baschang, Helmut Sturm, Jürgen Reipka or Ben Willikens? Were there connections due to Zeniuk’s Ukrainian roots?

O.K.:

In the second half of the 1990s, Ukrainian citizens could only obtain a German visa with an invitation from Germany. The processing time from the moment you presented your official invitation to the Kyiv Consulate of the FRG was about six months. So it was very, very difficult for Ukrainian citizens to attend the Academy of Arts in Munich with an application portfolio. Fortunately, my father was invited to the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1998 as a representative of a state-owned book publishing house, and he managed to take me along as his colleague. After the fair, we went to Munich for two days to visit a friend of my father’s, a journalist at Radio Freies Europa. This friend accompanied me to the secretariat of the Munich Art Academy, since I hardly spoke German. There they pointed me to a bookcase with the catalogs of the ac- ting professors of the academy. I was supposed to choose someone and write his or her name on the application folder. I don’t remember seeing Helmut Sturm’s catalogs on the shelf. I don’t think he was accepting new students at that time. Reipka, Willikens, and Baschang were “not painters enough” for me, so I chose Jerry Zeniuk and wrote his name on the portfolio. Nevertheless, I could not hand in the application portfolio to the secretary’s office, because it was generally much too early for applications. While leaving the art academy, my father’s friend saw a notice: that day there was to be a meeting in Zeniuk’s class. He made me go to the professor’s room. I knocked on the door, he was there and that’s how I met Jerry Zeniuk and showed him my portfolio. I only learned during that conversation that his parents had emigrated from Western Ukraine.

S.N.:

What was it like to re-locate yourself in the environment of the Munich Academy?

O.K.:

That was very difficult in the first year. My “old” friends in Kyiv laughed when I showed them during the semester break what you do in Munich at the Art Academy. My “new” friends in Munich also laughed when I showed them what one does in Kyiv. I was in between. The exhibition “Monet and modernism” in the Kunsthalle of the Hypo-Kulturstiftung then completely pulled the rug out from under the feet that I had brought with me from Ukraine. The Impressionists and especially Claude Monet, were highly appreciated in my country of birth both during the Soviet and post-Soviet periods, and I thought I knew everything about them. But it was precisely in this exhibition that I got a “new” perspective on Monet and his influence on contemporary painting: the motif. This exhibition suddenly gave me critical access to Gotthard Graubner, Robert Ryman, Blinky Palermo, Günther Förg, Sean Scully, Helmut Federle, Raimund Girke, and so on. There were not only charlatans here, as I was told in Kyiv.

S.N.:

“Not painter enough” in relation to the choice of your teacher in Munich is a good keyword. Can you explain that to me in more detail? What shaped your ideas back then in terms of what painting was?

And have your guidelines changed over time?

O.K.:

By “not painter enough” I mean when you color a shape or figure on the surface and don’t paint it; when you neglect the interaction of color; when you don’t respect the logic of color. At that time, my ideas of what painting is were shaped by my sensations when I painted. Painting is the application of color(s) by hand or some tool to a surface. That is, a painter deals with color, surface, and movement. We now know countless color systems, even the division of the surface has become a science, but the movement in painting remains “an unexplored forest”. The movements in the succession of time, in juxtaposition with the surface, were and are my guidelines for painting to this day. At the age of 17, I didn’t really know it yet, but I experienced the rhythm of applying colors intensely for the first time. In my mid-20s, I realized that rhythm gives form to the application of color.

S.N.:

There is a quote by Hans Platschek from his “Bilder als Fragezeichen” (1962) that comes to my mind on this:

“The spiritual in art is done with the hand. (…) For that is painting: a handling of things, of materials. A color is a thing, a line is a thing – they contain nothing but their own materiality, and only much later can one speak of water when one has used blue paint […]. Representational art, which is limited to rendering things as outlined, identifiable entities, as ‘words’, is unpainterly in that it must constantly deal with the splitting of its own essence, for the moment the painter uses his blue to represent a sky or water, he destroys the blue as a thing. It can even happen, as in some of Monet’s paintings, that despite the description of the haystacks or the cathedrals – not to mention the water lilies – the actual pictorial materials, in this case the color and its nuances, punch through the subject, absorb it, as it were, and exist independently on the canvas.”

Do you find your idea of painting in this?

O.K.:

Yes, absolutely. I was recently at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. At the exit in the last rooms before the café there are some images by Francesco Hayez. That hurt the eyes! It was like a wine with nothing right about it; after one sip, the palate tightens. With consideration for my eyes, I then took another look at Tiepolo’s “Temptation of St. Anthony” before leaving the Pinacoteca. Platschek uses the terms “representational art” and “identifiable entities” to describe the most important opponent of a painter, Cézanne called it “literature”, I call it: the image, in the sense of an imaginary image, a likeness, an image.

S.N.:

“El beso” by Hayez… Asger Jorn would certainly have made a wonderful modification of it.

O.K.:

Certainly. Asger Jorn has also invented three-sided soccer.

S.N.:

According to your preceding answers, the rhythm (in Platschek’s understanding this is – although clearly less systematically – the action) leads to the fact that color and movement manifest themselves to motifs/forms. To which motifs does the rhythm lead you? And is that completely open from the beginning or is there an idea of where you want to go?

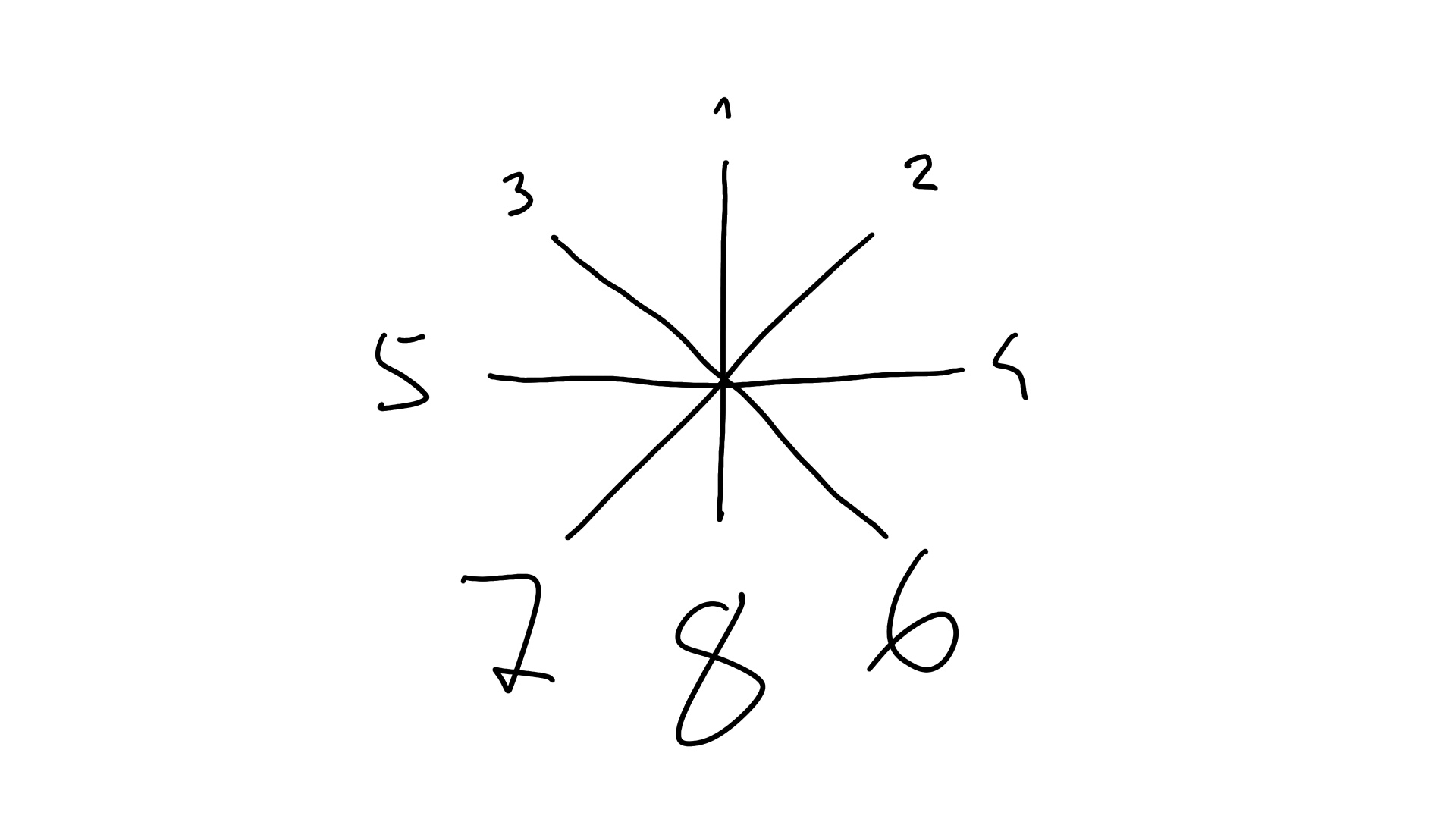

O.K.:

The rhythm brings out the primary qualities of painting. If the rhythm of the color on the surface is right, the painting is right. I have paint and a surface in front of me. I put the paint on the surface and get 1,2, or 8. I paint until I beat the surface!

Occasionally I compose my movement before I touch the surface – just as Marcelo Bielsa tells his team before the game when and where the players should move to impose the rhythm of the game on the opponent.

S.N.:

You speak of the imaginary image as your opponent in painting. Do you mean an image of the finished result in your head, i.e. an image that does not emerge from the rhythm, the painting process, but is fixed beforehand?

O.K.:

Yes, exactly: you can paint or color an apple, a kiss, or a rectangle. The surface of a work shows the viewer whether the form is painted or colorized. Malevich had an image of “Black or Red Squares”, of the “Farmer in the Field”, of “Red Cavalry” before he touched the surface with his brush. Mondrian, on the other hand, had a fixed idea about the means to conquer the surface, but he earned the motif during the painting process.

S.N.:

What does a composition look like in advance, i.e. before you apply the brush to the painting surface or the pencil to the screen? Is there anything you sketch out in advance, either textually or pictorially?

O.K.:

Before I apply the paint, I think about the movement: how and where do I paint on the surface? For more than 12 years, I have been working with other artists, musicians, and dancers to develop The Beautiful Formula Language – a language through which we write down our movement as we paint.

Unit, beat, and rhythm give form to the application of colors on a surface. The division of the surface and the procedure of movement while painting can be written down with the help of certain signs and symbols. This language makes it possible to understand the course of compositions, to realize the compositions and to design new ones.

S.N.:

In your reflections, you refer to Marcello Bielsa, the former coach of the Argentine national soccer team. Why?

O.K.:

I’m fascinated by Marcello Bielsa’s dynamic offensive soccer with its constant rotations between positions. His teams master different tactics, which they apply on the field as needed. I learn from this for my painting. My compositions are basically such tactical deployments, the order of movement that increases my chances of winning across the surface.

S.N.:

And how does the ladder in the work “Scala” come about? These are not successive decisions out of the rhythm, but a clear strategy. Doesn’t that contradict your statement that you want to conquer the image?

O.K.:

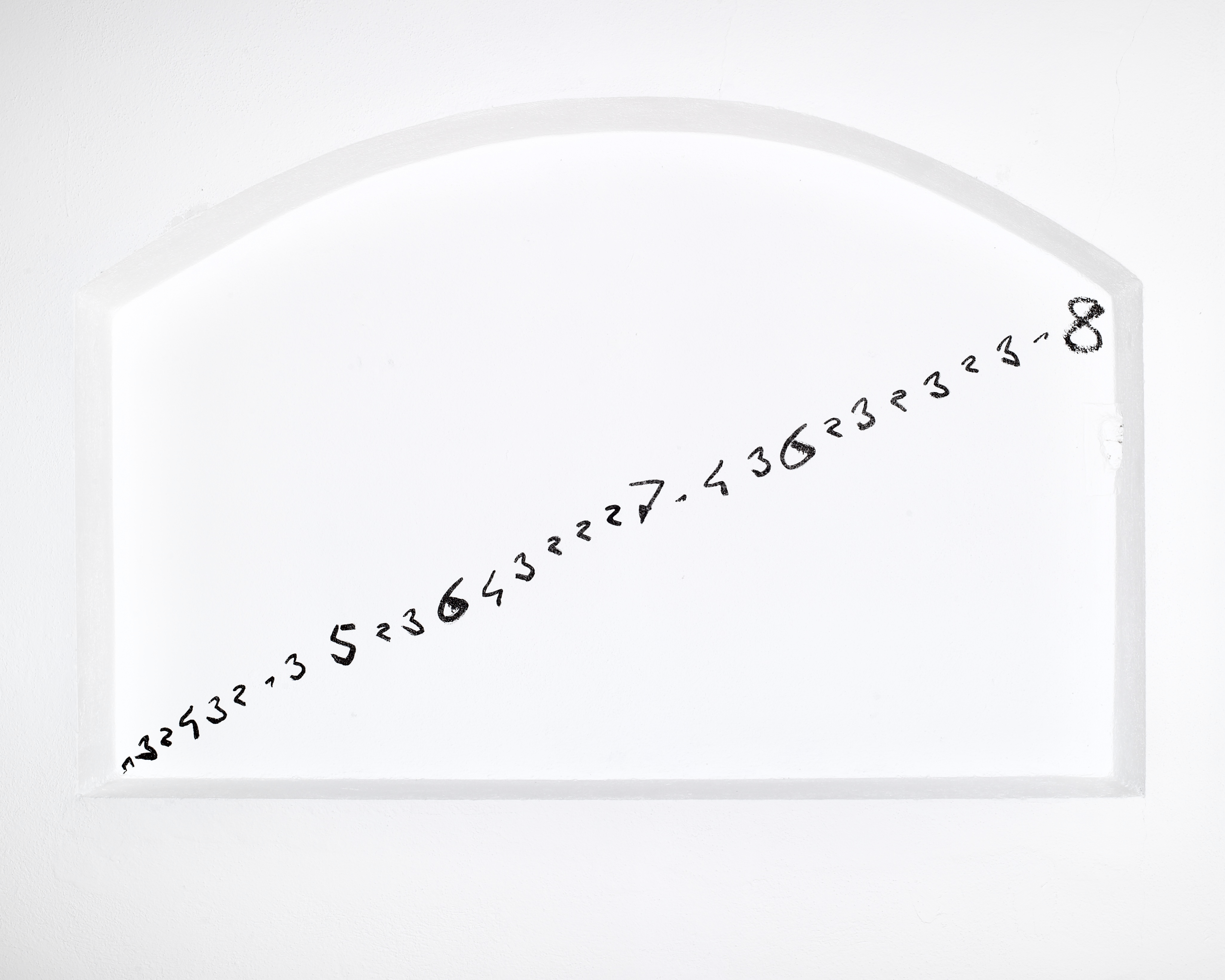

The composition “Scala” is built on a rhythmic motif 1,5,2,3,8. I start with the smallest entry in the lower left corner, move through three of 25 meters to the upper right corner, and complete the composition with the largest entry. I have a plan or, as you call it, a “strategy” for my movement on the surface, but no visual image of it! I don’t have a particular ladder in mind that I want to depict. I have a composition that gives me a route, but I see how I move on the surface as I paint, and I react to that spontaneously. All the characters that emerged between the rhythmic motif were spontaneous.

S.N.:

Can you explain to me what fascinates you about numbers and what meaning they convey to you?

O.K.:

Numbers mean numbers, the number one means one, the number two means two, the number three means three and so on. They are created as I paint. I apply the smallest size of paint to a surface and get one, I apply the largest and get eight. Numbers do not lie.

S.N.:

Above you talked about The Beautiful Formula Language. Did you develop this language together in the group The Beautiful Formula Collective? I ask because reflections on this can be found very clearly in your work, but I think the references are less obvious in the other group members. Doesn’t each of you have your own language that you bring to the group? So: who developed the “grammar”? You in the collective? Or are you a kind of Marcello Bielsa for the collective, who sets the language and communicates the strategy in this language before the “game”?

O.K.:

If each of us had our own language in which to communicate, we would arrive back at the Babylonian confusion of languages. Painting is a visual language that releases communications between painters and viewers. Just as German, English or Ukrainian enable verbal or written communication between two or more participants. Whether one uses an expletive, writes a novel or a poem, or creates a painting with respective languages depends on the way one begins to communicate. I initiated the development of The Beautiful Formula Language, but it is a group language. The Beautiful Formula Language allows me to paint compositions of others, and for others to paint my compositions. The “grammar” of the language was developed through group dynamic processes. Signs and symbols emerged only after a member of our group had written down a composition of his or her own. Just as “ordinal number” first appeared in the composition “Doppelgänger” by Karina Bugayova, or “{ n } polygon with n edges” resulted from the composition “Backjump” by Daniel Geiger. Each of us who has composed a composition is a kind of Marcello Bielsa.

S.N.:

When I attended your painting action in the Lothringer 13 in November 2023, I had the impression that the basic initiative comes from you, but that you then communicate among yourselves and in each case with the musicians and the dancer intuitively-playfully and spontaneously. The playing together, and also against each other then goes beyond the boundaries of a single common language system.

O.K.:

I have learned a lot and I am still learning from Steve’s music for my painting. For this reason, I contacted Steve Coleman and initiated together with The Beautiful Formula Collective what is already our fourth joint interdisciplinary performance. These performances show that The Beautiful Formula Language not only enables the realization of artworks in different areas of the visual arts, but it is also effective across media. We are less interested in the development of a language system, and much more in the diversity of our compositions. The Beautiful Formula Language is the tool that provides us with a vivid entry point and a recognizable conclusion when painting.

S.N.:

Of course, through your association and close exchange, you have developed a “common” language. I know this from other groups as well. But there this happened rather playfully, intuitively, as with children who make a language their own through imitation and then fill it out with their respective personalities. You are already one step further here, so – to stay with the comparison – you have “gone to school” and have developed an awareness of grammar or even your own play form of grammar and written it down. What moved you to go beyond the “naive” variant?

O.K.:

No one before us has composed the movement in painting. The current flood of images and their potential violence have caused us to pass over naive variants of image service and reduce them to the use of the beautiful formula.

S.N.:

I have dealt more intensively with the Munich artist groups of SPUR, WIR, SPUR-WIR, GEFLECHT and KOLLEKTIV HERZOGSTRASSE, which were influenced by CoBrA, and in which there were close overlaps among the members, so that one can also speak of a certain group genesis. Within the groups there were very heated discussions about painting, the function of the group, and the position of the individual in the group, i.e. the conflict individual/group. This went so far that groups also broke up as a result. These experiences were certainly one reason why different models were tried out with the different groups: For example, at SPUR there were essentially three painters, a sculptor and an “activist” who generally continued to work individually while also influencing the group style with their respective individual styles. Sometimes one was in front, sometimes the other. Collectively, mainly magazines and actions were created, but also individual group works as well as the so-called painting game, for which leaves went around in a circle according to written rules.

GEFLECHT was much stricter. Here there was an explicit group style based on theoretical considerations. The collective works were created in a relatively “orderly” fashion according to a “pattern” to which the individual artists had to subordinate themselves.

In the KOLLEKTIV HERZOGSTRASSE then the “free” group painting, as it was applied in rudiments in some collective works of the group SPUR, was set up anew and realized in its probably most open and spontaneous way. In a text, the painter Heimrad Prem describes the principle: “If about 10 people paint on a picture, then it is obvious that at first everyone takes a color. Clearly, not everyone can paint a specific place on the canvas because his color must occasionally appear in the whole picture. Besides, there is little point in painting complicated objects, because, after all, everyone can paint in everywhere, – that is, destroy or underline. The individual must come to terms with the fact that he cannot assert himself. But he can paint along. […] It also follows quite naturally that one can use simple forms, namely spots and lines. The spots are the mass and bring mood. The lines are destruction, movement or drawing. Through the overlapping of the individual destruction processes, the complicated structure arises by itself, so it does not have to be constructed.”

In all the cases mentioned, the group provided orientation and support for its members, both in terms of developing their own visual language and in terms of positioning themselves within society and the art market. It thus offered a protected space and at the same time enabled a more self-confident appearance to the outside world. In the process, it actually became part of the art market, so there were gallery exhibitions of the groups from which works were sold.

How do these historical groupings compare with you? How do you define the group?

O.K.:

The Beautiful Formula Collective is about painting and creating collective works based on The Beautiful Formula Language. We use the combination of spontaneity, improvisation, and rhythm in applying colors to surfaces. The Beautiful Formula Collective paints not only in the studio, but also in public spaces.

S.N.:

Is there a close core and guests?

O.K.:

There is a core of the group, which currently consists of eight artists: Karina Bugayova, Daniel Geiger, Gonghong Huang, Veronika Wenger, Thomas Rieger, Alina Sokulska, Michael Wright, and myself. By “core” I mean those who are actively involved in the development of the language, the compositions, and the paintings created together. This core consists not only of those who have been there from the beginning. Sometimes after a workshop we do a performance with the workshop participants called The Beautiful Formula Syndicate. In Syndicate, up to 20 artists have realized compositions together with us on one surface.

S.N.:

So, you are relatively open to those who are interested?

O.K.:

Of course, we are open to all who are interested in our project. Our youngest participant, who is part of the core of The Beautiful Formula Collective, has only been with us for a year.

S.N.:

And what function does the group have for the individual member?

O.K.:

I can’t answer that question for everyone. I love to paint. When painting, we share the immediate experience of fighting against the surface, and that enriches me. By working with the collective, I deepen my knowledge of movement in painting. That’s why I founded and am a part of The Beautiful Formula Collective.

S.N.:

Is it always just a fight against the surface that you lead, or is it not sometimes also a (productive) fight against the “disturbing” fellow painters in a positive sense? Disturbing in the sense that you cannot settle too comfortably in one direction, but are challenged to react and to reconsider what you have achieved?

O.K.:

On the contrary, it is often “more comfortable” to paint in a group than alone. Of course, I am sometimes negatively surprised and sometimes positively impressed by the entries of the fellow painters and am challenged to react to them spontaneously. Occasionally we “fight” on the surface, but we don’t fight each other. We have a common opponent: the surface.

S.N.:

How does the environment/market react to the group or you to the market?

O.K.:

The Beautiful Formula Collective challenges the art business. Not only do we have regular requests from collectors, we also collaborate with various exhibition venues such as galleries and museums. They acquire our works and invite us every now and then for a live painting performance in front of an audience. The Beautiful Formula Collective has performed and exhibited in Kyiv, Singapore, Zurich, Istanbul, London and Wuhan, to name a few stops. This year we have already received requests from Athens, Istanbul, Augsburg, and Munich.

S.N.:

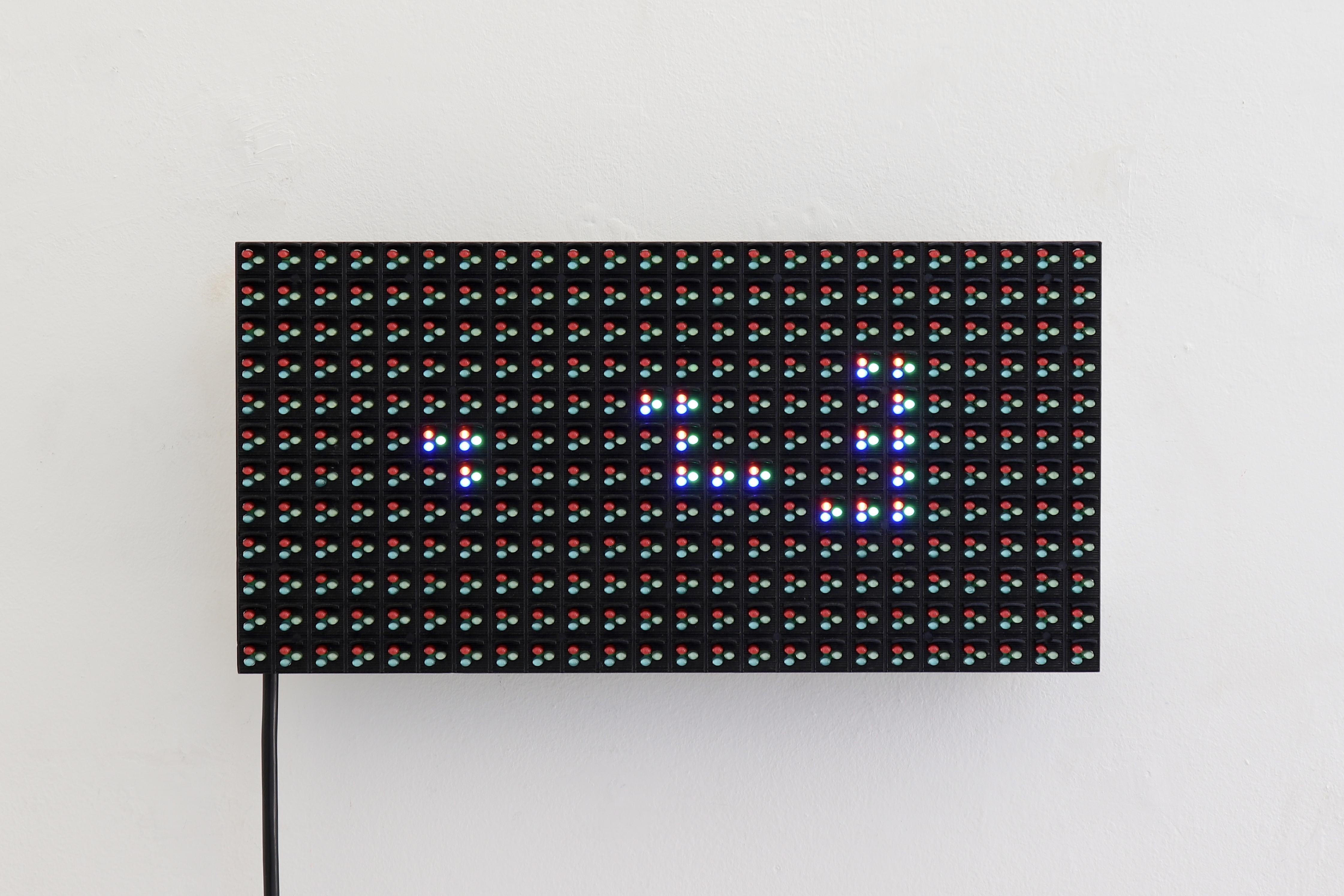

Especially now in comparison to the works you mentioned above, the question of the screens comes to mind. Where do you see the advantage and how do you compensate for the lack of materiality?

O.K.:

I distinguish eight basic components of painting: color, surface, movement, time, space, light, fabric (various materials), and finally the painter. Here, space and light are elements of the environment in which a painting (form) is created; color, surface, movement, time, fabric and painter are elements of both an environment and a painting.

The experience I have had in attempting to paint with digital means has changed the relationship of some of these eight elements.

In the case of painting processed by processors, space remains an element of the environment.

In contrast to analog painting, light in digital painting is not just an element of the environment, but also of the painting. A surface of paper, fabric, stone or wood absorbs the color of the light of the environment. In the case of the surface of a screen, its own electromagnetic radiation is added to the light of the environment.

As with analog painting, in digital one keeps the two origins for the use of color apart: color space and colorant. The colorant of the screen along with the color space stored on the working memory determine the color tone.

The surface in painting is understood to be a painting support. For applying colors to a surface, two essential properties of the surface are important: shape of the surface and the quality of the surface. Here there is only one difference between analog and digital painting: there is no possibility to change the fundamental material of the surface of a screen by using digital tools.

Also, in digital painting there are two different types of movement: movement in space and movement on the surface of the painting. The relationship to time and time zones on the surface also remains the same, although the paint and the base material of the surface of a screen are made of one and the same material.

In analog painting, I have the ability to apply several fabrics on the surface of a painting support. In digital painting, on the other hand, only the materiality of the screen remains.

Likewise, a painting developed by digital tools always refers to the painter and the communicated meaning.

S.N.:

And why do you limit yourself to black and white?

O.K.:

I distinguish five primary colors in both analog and digital painting. The decision whether I or we proceed with one, two, or five colors against the surface is up to the composition and the materiality of the screen.

Oleksiy Koval, 2018

LED, 16 x 32 cm

Karin Wimmer Contemporary Art, Munich

Photo: rhythmsection.de

S.N.:

Are the results “only” documented on film, or are there forms of presentation that can flow back into exhibitions as “flatware”?

O.K.:

In digital painting, too, a painting is the result of a painting process. All of our works that we have painted in the studio or in front of an audience with digital tools exist as files and are exhibited as “flatware” for a while after the performance.

The Beautiful Formula Collective 2021

Daniel Geiger, Oleksiy Koval, Thomas Rieger, Veronika Wenger

Galerie der Künstler*innen, Munich

Photo: Digital Art Space, Munich

S.N.:

In the Lothringer 13 last winter, there were many different states within the work. Also complete “erasures”, i.e. completely black or white areas on which the “painting process” seemed to start completely anew.

O.K.:

What you call “erasures”, I would call “reaching monochrome areas”. Every good painter occasionally achieves monochrome areas when painting. With monochrome surfaces, there is no subject other than color. The color appears in and of itself, in its original strength. And if our eyes say during the painting process that a monochrome surface would be good here now, then we paint it.

S.N.:

How do the collective painting actions come to an end? Who determines when a painting is finished?

O.K.:

A painting is complete when everyone is satisfied with the result. We have compositions, which are kinds of traffic regulations to avoid accidents, but everyone is allowed to break the law for the love of the completed painting. You run a red light when you have to catch a bus. There are no standard recipes for finding an end when painting. Sometimes the entry from Veronika, Daniel, or Thomas sits so that none of us wants to keep painting. Sometimes we stop because the composition is over. Sometimes we stop because we have reached a monochrome surface. In Lothringer 13, we responded directly not only to what was happening on the surface, but also to Alina’s movement, Kokayi’s singing, and Steve’s music. All of this determines when the painting is complete.

S.N.:

And how do you find the title?

O.K.:

There is also no uniform method when it comes to titles. A title can be a rhythmic motif, as in my composition “1,1,1,2,3”; a title can be a certain movement, as in Daniel Geiger’s composition “Back Jump”; often we have painted Veronika Wenger’s composition under the title “French Wine” – we want to paint everything!

And if we can’t come up with anything, then we paint “Untitled”.

The Beautiful Formula Collective 2016

Karina Bugayova, Daniel Geiger, Oleksiy Koval, Veronika Wenger

Ink on FPY, 80 x 70 cm

Photo © Dmytro Goncharenko

S.N.:

Theoretically, one could also “cheat” in the digital and restore earlier states that seem better to one?!

O.K.:

We regularly work with such “cheating” in both digital and analog painting. I would call it “color-take-away use”. But in digital painting, it’s actually easier to take away the color because you’re only working with one materiality, the materiality of the screen.

S.N.:

What remains of an action apart from the “classic” film, or the work, or exhibition of photography? In which format is the work ultimately stored?

And connected to this: if I now want to “hang up” a digital work at home, or put together a “retrospective” exhibition, how would I have to proceed? The works also depend on certain hardware that may no longer be available or that I, as a collector or exhibition institution, would first have to obtain. Is there detailed documentation for each work so that it could be “rebuilt” in its original state in the future?

O.K.:

From such actions a painting remains, a digital painting, saved for example as JPEG, GIF, PNG or as a video file. The collectors or institutions get a USB stick, or the file is sent by mail. The works depend less on a specific hardware, but much more on the resolution, proportions and color mode. These specifications are stored directly in the file, such as: 1920 x 1080px; 16:9; MPEG4; HD (1-1-1) and so on. In this case, we would need a device that can play this file with these size ratios and in this color mode without distortion. Whether the digital surface that reproduces our painting has a size of 25 x 14 centimeters or 25 x 14 meters is only of importance to us when we work with exhibition spaces. A collector bought a work of mine still at the first exhibition “Binär” in 2018. In the meantime, he has replaced the TV three times and proudly reported to me that my painting can be seen very well and without losses even on his last screen. Since 2020, I have repeatedly exhibited my digital painting on screens in public spaces. There are various manufacturers and various devices, which are mounted in streetcars, subways, or even in train stations or shopping malls. Some screens are already 10 years old, some are brand new, but they reproduce my painting flawlessly.

S.N.:

What is your goal in offering workshops, which are also open to “lay people”?

O.K.:

In the fight against the image, we need idealistic support. The goal of our workshops is to make the difference between painting and coloring clear to the participants. It is about painting. Workshop participants will learn how to paint with a combination of spontaneity, improvisation, and rhythm. It is about creating collective works based on The Beautiful Formula Language.

S.N.:

Finally, a big question, after you have already spoken of the potential danger of the flood of images: Is there a “political” claim in your group painting? Some people talk about the group as a micro-society and the chance to try out new ideas and models within this framework. Do you also have a background of this kind?

O.K.:

We distinguish a painting from an image. We distinguish bad painting from good painting. Distinctions of gender, nationality, or age in painting are not important to us. In our painting we bring together what is separated by social and political institutions or by social narratives. In this respect, we practice a directly “political” claim.

From: Oleksiy Koval, Acht, published by Kastner, Munich 2023.